On October 20th, housing providers, policymakers, funders, and community partners gathered for the fourth annual Housing Symposium, hosted by United Way Halifax and the Nova Scotia Non-Profit Housing Association. I had the privilege of being invited to speak at this years’ Symposium, presenting my graduate research regarding how Canadian courts interpret “adequate shelter” and how those interpretations compare with frontline shelter providers’ perspectives. With support from the Turner Drake team, I had the opportunity to expand on this research to include predictive data modelling to better understand the systemic factors associated with homelessness in Halifax and across Atlantic Canada.

Background

International human-rights frameworks and Canadian case law recognize that evictions from homeless encampments may raise human-rights concerns when no adequate and sufficient shelter alternatives exist. But what counts as “adequate” or “sufficient” in practice? This question directly informed the basis of my graduate research.

To explore this, I conducted a comparative thematic analysis of 13 legal decisions from Ontario and British Columbia involving encampment evictions on public land. By coding judgments for themes (and for direct references to adequacy and sufficiency) I examined how courts evaluated shelter conditions across jurisdictions. To complement this analysis, I surveyed 51 emergency shelter staff in Nova Scotia, Ontario, and B.C. to better understand how those working directly with unhoused people define adequacy in day-to-day practice.

Findings

Cases that engaged more deeply with shelter adequacy were far less likely to result in eviction. Decisions that did not authorize eviction referenced adequacy-related terms an average of 17.9 times per case, compared to 4.6 references per case in decisions that did allow eviction.

Across the cases analyzed, courts that permitted eviction tended to focus more heavily on the number of available beds (sufficiency), while placing less emphasis on whether those beds were appropriate or accessible—for example, considering factors such as admission requirements, safety, proximity to supports, or suitability for different populations.

Survey responses from shelter providers highlighted a broader, more nuanced understanding of adequacy. Staff commonly referenced safety, dignity, harm-reduction, trauma-informed practice, and culturally appropriate care as essential components of an adequate space. Many also emphasized that adequacy is inherently subjective: what is suitable for one person may not meet the needs of another. These frontline definitions aligned closely with United Nations adequacy standards, which include standards such as privacy, security, cultural appropriateness, and proximity to services.

Overall, the research points to a consistent pattern: while adequacy plays a central role in determining whether encampment evictions comply with human-rights standards, its definition and application vary widely across legal decisions. Although this research does not offer a single answer to “what is adequate shelter?”, it identifies a clear gap and an opportunity for more consistent legislative or policy guidance to support decision-making in this area.

Expanded Research Context

Expanding on this research, we examined how data can help clarify the relationship between local socioeconomic conditions and homelessness. Made possible by the guidance of my colleague, Jigme Choerab, Manager of Turner Drake’s Economic Intelligence Unit, we used applied logistic regression to analyze Statistics Canada’s General Social Survey (2019) alongside local “By-Name List” data generously provided by the Affordable Housing Association of Nova Scotia (AHANS). This approach allowed us to explore broader patterns that may influence, or move in parallel with, homelessness at the community level.

The Social & Economic Cost of Homelessness

We sought to understand how even a single experience of homelessness may relate to long-term economic and health outcomes. The analysis suggests that individuals who have experienced homelessness tend to face reduced earnings, poorer health indicators, and lower housing stability over time. These findings are correlational rather than causal, but they highlight meaningful associations between homelessness and a range of social and economic outcomes.

| Outcome | Never Homeless (%) | Ever Homeless (%) | Social & Economic “Cost” |

| Home Ownership | 80.2 | 15.0 | Smaller property tax base, higher demand for housing supports |

| Income ≥ $50,000 (before tax) | 35.9 | 1.0 | ≈ $12,000–$15,000 lost income tax revenue per person/year |

| Post-secondary Education | 60.9 | 17.5 | ≈ $300,000 lower lifetime earnings potential |

| Marital Status (married, common-law) | 69.9 | 16.7 | Greater risk of social isolation; higher service needs |

| Medication for depression/sleep | 22.7 | 76.9 | Increased healthcare use and public health cost (~$2,000–$4,000/year) |

What Drives Homelessness in HRM?

Among the variables examined, population growth showed the strongest correlation with increases in homelessness. While growth itself does not directly cause homelessness, rapid in-migration can place pressure on housing supply and local services, particularly when income growth and new construction do not keep pace.

| Driver | Approx. Impact on Homelessness (per 1% increase) |

| Population Growth | +8.3% |

| Home Prices | +0.6% |

| Shelter Beds | +0.7% |

| Unemployment | +0.55% |

| Housing Starts | +0.06 |

Rising home prices and unemployment were also associated with higher homelessness rates. Increases in shelter-bed numbers tended to reflect reactive responses to growing demand rather than a decrease in underlying need. Taken together, the data reinforces that homelessness is shaped by multiple interconnected factors, creating opportunities to think more holistically about growth, affordability, and income stability.

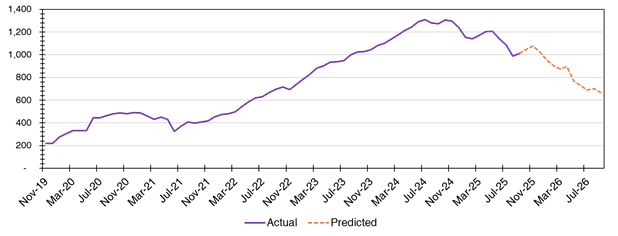

Predicting Active Homelessness in HRM

To explore near-term trends, we modelled a conservative scenario in which population growth slows, unemployment declines, and affordability moderately improves over the next year. Under these assumptions, the model points to the possibility of a gradual reduction in active homelessness in HRM. As with any predictive modelling, these results illustrate potential trajectories rather than forecasts.

Early signals suggest some stabilization, and there is room for continued progress. Behind each data point are individuals whose experiences are shaped by the systems and decisions in place today.

Conclusion

Homelessness is a complex, interconnected systems challenge. Grounding our approaches in both qualitative insight and quantitative evidence helps communities plan, invest, and prioritize responses that support long-term stability and well-being.

Predictive analytics offer one tool among many to move beyond crisis response toward prevention. For planners, policymakers, and service providers, these combined methods support earlier, more informed decision-making.

Presenting this research at the Housing Symposium was both humbling and encouraging. It reinforced that meaningful progress emerges where empathy and evidence meet. At Turner Drake, this intersection is at the core of our work—we are committed to advancing data-driven insights that help communities, governments, and service providers plan more effectively. By combining rigorous analysis with a grounded understanding of lived experience, our team continues to support partners across Atlantic Canada in building solutions that move beyond crisis response toward long-term stability and housing security. If you’re looking to strengthen decision-making with evidence-based insight, Turner Drake’s team is here to support your work. Reach out to Katie or the team (902)429-1811 or 1(800)567-3033.

Katie Brousseau leads strategic policy planning work at Turner Drake. Katie brings a wealth of experience from the not-for-profit sector, with a focus on social enterprise, housing, and community development.

For more information about how you can benefit from the unique expertise of our Planning & Economic Intelligence team, contact Katie at (902) 429-1811 or .