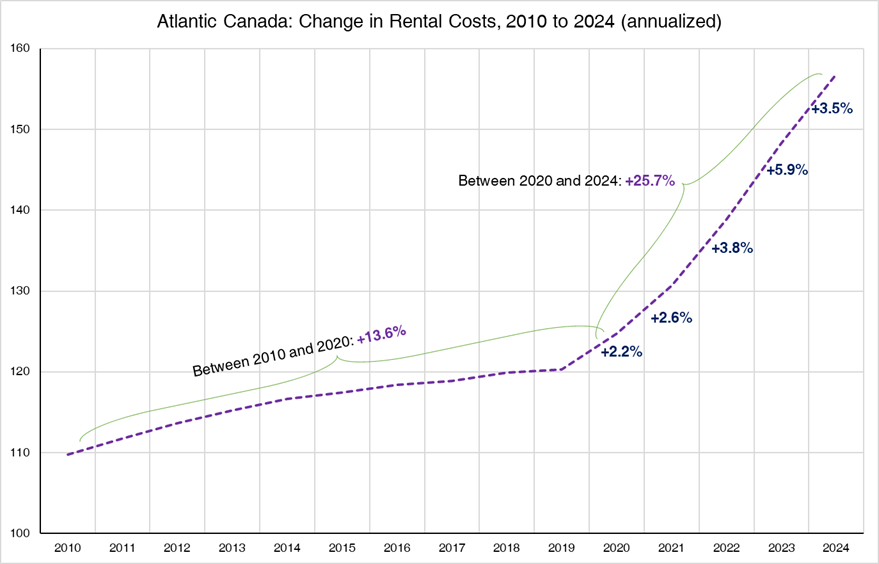

Global affairs have dominated the media of late, but the challenge of rising living costs continues to shape domestic politics. It is particularly evident at the local level this time of year. If you own real estate in Nova Scotia, last month you received your updated property assessment, and at this point your local municipal council is likely deep in the throes of setting their budget and tax rates.